|

Courtney Jones, a Chicago real estate agent and developer, has the perfect analogy for racial inequity in modern-day real estate: Picture a game of Monopoly, and then imagine that your opponent got to circle the board 400 times before you were allowed to play.

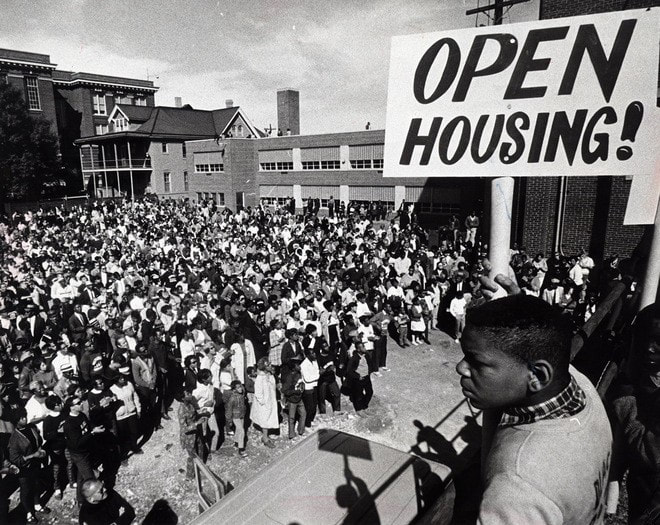

“How much would that affect your ability to be successful at the game?” he said. Black people have been treated inequitably when it comes to the American dream of homeownership, as ugly practices like redlining, segregation and, to this day, inequity in lending prevent them from having the same opportunities as their white counterparts. As the country’s attention has turned to systemic racism following George Floyd’s death and nationwide protests calling for action, the movement is sparking conversations in the Chicago-area real estate industry about the need for change. “It’s just time to assist the rest of mainstream white America to really become conscious of what its brethren have been dealing with,” Jones said. “Just because the shackles aren’t physically on people’s wrists and neck doesn’t mean it’s really a level playing field in the socioeconomic space.” There are encouraging signs of progress in the real estate sector: This year, the Chicago Association of Realtors elected the first Black female president in its 137-year history, while Jones is the city’s first Black “receiver” of a downtown high-rise as part of a city program in which developers are hand-picked to rehabilitate buildings seized by the government over, for instance, building code violations. Courtney Jones, president of the Dearborn Realtists Board, an organization focused on eradicating racist practices from Chicago real estate, stands outside one of his listings, the Pittsfield Building at 55 E. Washington St. on July 6, 2020, in Chicago. (Erin Hooley / Chicago Tribune)But equality seems a long way away. Change is needed in lending practices, equitable building across neighborhoods and investment in communities where the effects of redlining and other discriminatory practices linger, Black industry leaders say. But, they add, they cannot shoulder the burden alone. “You cannot sit on the sidelines,” said Nykea Pippion McGriff, president-elect of the Chicago Association of Realtors. “You have to be a player to change the game.” The most recent debate centers on removing the term “master” from listings when describing a home’s largest, primary bedroom or suite because of the word’s association with slavery. Houston Realtors was among the first to make the move in late June, and the issue has been raised in Louisville, Kentucky, Washington, D.C., and here in Chicago. Local brokerage @properties told its employees at the end of June that it would phase it out of company materials. “It seemed like a very obvious, easy thing to do,” said @properties co-founder Thad Wong. “I don’t think changing this word is going to change systemic racism in our society. But if it’s a word that is negative for any group, I don’t know why we wouldn’t put effort into changing it.” At the state level, Illinois Realtors follows U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development guidance, “which says the term is not discriminatory,” said Illinois Realtors spokesman Anthony Hebron. The Chicago Association of Realtors said it “support(s) inclusive language” and its board members are discussing the issue. Same goes for the Midwest Real Estate Data (MRED), the Lisle-based multiple listing service that serves much of the Chicago area, a spokesman said. Dearborn Realtists, the country’s oldest African American real estate trade association formed in 1941 in Chicago, is set to discuss the topic at its next board meeting, said Jones, the association’s board president, who also co-owns Chicago Homes Realty Group & Property Management and serves as executive director of the nonprofit Black Coalition for Housing. “A lot of negative history is attached to that word,” Jones said. “The subliminal messaging just continues to perpetuate a message of inferiority, or submission.” But adjusting language can only go so far, said Pippion McGriff, who is also a broker with DreamTown. “I think at this point, we’re beyond words,” she said. “We need more specific action. Personally, I think it’s a Band-Aid.” Pippion McGriff got into the real estate business 15 years ago after buying her first home. Learning about grants and other funding options she’d never heard of proved an eye-opening experience. Realtor Nykea Pippion McGriff wears a face mask to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 as she turns off a stairwell light while showing a home in the Avondale neighborhood May 2, 2020, in Chicago. (John J. Kim / Chicago Tribune)So was seeing discrimination firsthand against buyers with federal housing choice vouchers; five years ago, Pippion McGriff had clients with a voucher looking for a three-bedroom home in the South Loop or Loop who were repeatedly turned down with no explanation. “Brokers look for ways to circumvent it, but they need to learn that source of income is a protected class,” she said. “The first question was, ‘Is this Section 8?’ Well, yes, and it’s also a protected class with pretty much guaranteed income for your client. But I was unable to find them a property in the area they wanted to be in. It was completely disheartening.” It’s not enough, either, to simply treat everyone the same now, industry leaders said — Black people are still too many laps behind on the metaphorical Monopoly board. “We talk a lot about gentrification and the result of that, but the communities need more access to capital,” Pippion McGriff said. Loans for rehabbing blighted properties, alternative lines of credit, and funds for first-time home buyers are key areas where investment is needed, she said. Changes in lending practices based on factors like credit scores and risk calculations — with the consequence often being a Black family paying more for the same loan because they’re considered a riskier borrower — would give disadvantaged borrowers a fair shake, Jones said. “A clean slate, to me, would mean everybody has access to capital at the same cost,” Jones said. But that’ll be difficult in a post-pandemic world, where spikes in unemployment have lenders changing guidelines or requiring more money for a down payment, said Sheila Dantzler, a real estate agent with Jameson Sotheby’s International Realty who also builds and rehabs buildings in her Bronzeville neighborhood. While the percent difference might seem small, the cost of a higher-interest loan over its decades-long term could come at the expense of college tuition, retirement savings or other means of increasing wealth. When the pattern repeats across generations, the loss only grows. Over the past four decades, the median home in redlined neighborhoods in Chicago netted $232,000 less in home equity — about half what the median home in greenlined neighborhoods gained, according to a June report from real estate brokerage Redfin. “If society cares about all of its members, then it’s important we push for this proportionate economic benefit for Black people to be made whole,” Jones said. “We’ve seen restitutions and reparations for different cultures because of the heinous things those people have been subjected to; and we’re the last who haven’t received that.” Tougher enforcement of fair housing laws, coupled with education on what discriminatory practices entail, would go a long way. NAR has already ruled that secretive “pocket listings” — homes kept close-to-the-chest, off the market and offered only to a choice few — should not be allowed, seeking to level access to top listings. The city has made solid strides with efforts like the Neighborhood Opportunity Fund and Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s Invest South/West initiative — which is meant to pump $1 billion from city agencies, private investors and tax-increment funding into 10 Chicago neighborhoods in three years. Dantzler was one of five builders selected for the 3rd Ward Parade of Homes initiative, which used city-owned lots to build 42 single-family homes with high-end finishes in Bronzeville over the past three years. “But often, it takes a really long time, and there’s a high barrier to get into it,” Dantzler said of the city-funded programs. “If it’s city land, they want environmental tests and appraisals, which can cost thousands of dollars before you even get approved and take up to a year before you even start.” Real estate agent Sheila Dantzler stands in her under-construction salon July 12, 2020, in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. (Erin Hooley / Chicago Tribune)Real estate firms should also reexamine their own methods of tracking agents’ success to encourage buying and selling in lower-income neighborhoods, Dantzler said. If brokers are judged on the total dollar amount of their sales, an agent who sells 25 homes in pricier North Side neighborhoods will outrank one who sells 25 homes on the South and West sides. “We can’t abandon our communities and go somewhere else to try and make more money, but we’re doing the same amount of work,” Dantzler said of South Side real estate agents. “I’ve lived here, my parents lived here. These are my neighbors.” The industry also needs to take a hard look at who is leading it, Pippion McGriff said. “There is a lack of diversity in upper levels of leadership,” she said. “Look at how brokerages are attracting and promoting talent. Diversify your network. Those are very specific actions you need to take in addition to changing wording on a listing.” The Chicago Association of Realtors has scholarships for people of color who want to study real estate or further their education, and it is also working on initiatives like The 77, a diversity committee with a member from every Chicago neighborhood focused on fair housing and economic development. It’s just one way for allies to join in the fight, Pippion McGriff said. “Figure out what’s happening in all the different communities that you may not sell in as a Realtor,” she said. “But you’re a Chicago broker, so you should have a certain knowledge of what’s happening in the city.” There are other signs of progress, like Jones’ receivership. He was chosen as part of a city program to fix the lower half of the Pittsfield Building in the Loop, repairing its crumbling facade, replacing windows and making other cosmetic changes. Dearborn Realtists began working with the city in 2017 to train more Black developers and mom-and-pop investors in the receivership process, opening up opportunities for 330 recruits, Jones said. But real estate is just one factor in a system in need of a larger overhaul. Families often decide where to live based on the quality of nearby schools and the level of violent crime, Dantzler said. Better schools will draw more buyers to neighborhoods and give children better opportunities that provide an alternative to a cycle of violence that has plagued disinvested communities for generations, she said. “Where schools aren’t good, parents don’t feel safe sending their kids there, so they move out of the neighborhood,” she said. “And then you have neighborhoods that are somewhat abandoned and just never able to rebound. That translates into property values and appraisals.” She and her husband strive to make their community better, building new homes and, most recently, renovating a commercial building with the hopes of bringing more retail to Bronzeville. She recognizes that it’s important to keep the community affordable for the people who have lived there many years, but to her, vacant lots help no one. “The motto for our business is improving the neighborhood one vacant lot at a time,” she said. Still, they face setbacks that developers on the North Side don’t. While it costs the same to build a home in Bronzeville as it does in pricier areas like neighboring Hyde Park, the sale price is far less, Dantzler said. With lower margins, lending guidelines are tighter. “They think, ‘I could build the same house 5 miles up and triple my profit,‘” she said. “So it’s hard to find committed developers.” Still, there’s a sense going around that maybe, just maybe, the time for real change has come. “There’s a lot of tension, and I think we have to remember we’re all in this together,” Pippion McGriff said. “It’s one human race, acknowledging the problem and working together for a solution to provide equity to all members of our city.”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

- iMove Chicago

- Real Estate School

-

Laws

-

CRLTO

>

- 5-12-010 Title, Purpose And Scope.

- 5-12-020 Exclusions.

- 5-12-030 Definitions.

- 5-12-040 Tenant Responsibilities.

- 5-12-050 Landlord’s Right Of Access.

- 5-12-060 Remedies For Improper Denial Of Access.

- 5-12-070 Landlord’s Responsibility To Maintain.

- 5-12-080 Security Deposits.

- 5-12-081 Interest Rate On Security Deposits.

- 5-12-082 Interest Rate Notification.

- 5-12-090 Identification Of Owner And Agents.

- 5-12-095 Tenants’ Notification of Foreclosure Action.

- 5-12-100 Notice Of Conditions Affecting Habitability.

- 5-12-110 Tenant Remedies.

- 5-12-120 Subleases.

- 5-12-130 Landlord Remedies.

- 5-12-140 Rental Agreement.

- 5-12-150 Prohibition On Retaliatory Conduct By Landlord.

- 5-12-160 Prohibition On Interruption Of Tenant Occupancy By Landlord.

- 5-12-170 Summary Of Ordinance Attached To Rental Agreement.

- 5-12-180 Attorney’s Fees.

- 5-12-190 Rights And Remedies Under Other Laws.

- 5-12-200 Severability.

- Illinois Eviction Law (Forcible Entry And Detainer)

- Illinois Security Deposit Return Act

-

CRLTO

>

- Today's Cool Thing

- Social Media